Gender-fluid fashion professional Aaron Myers explores what it means to be queer today

An electronic soul beat flows through the headphones of 24-years old Aaron Myers as he waits for the J train. The music transforms the daily commute to the office into an immersive, independent documentary of Aaron’s own creation. The train takes him over the Williamsburg Bridge, the cityscape of New York City serving as the backdrop and a reminder of life in the city.

Delays come and go, allowing the momentum created by morning rush hour to lose steam. Upon arrival to Canal Street, Aaron transfers to an express train which takes him to 42nd St./Times Square. He walks through the landmarked station to his office, where he works as a trend and concept designer at the renowned fashion brand Vince Camuto.

Dressed in a t-shirt with a tiger face as its focal point, bloomers, knee-high socks, and round glasses, Aaron is an intriguing, visibly queer advocate of gender-fluid fashion.

He serves as a strong representation of contemporary young adults in a major metropolitan city: AMAB (Assigned Male At Birth, term for

In fact, as of 2018, 11 million

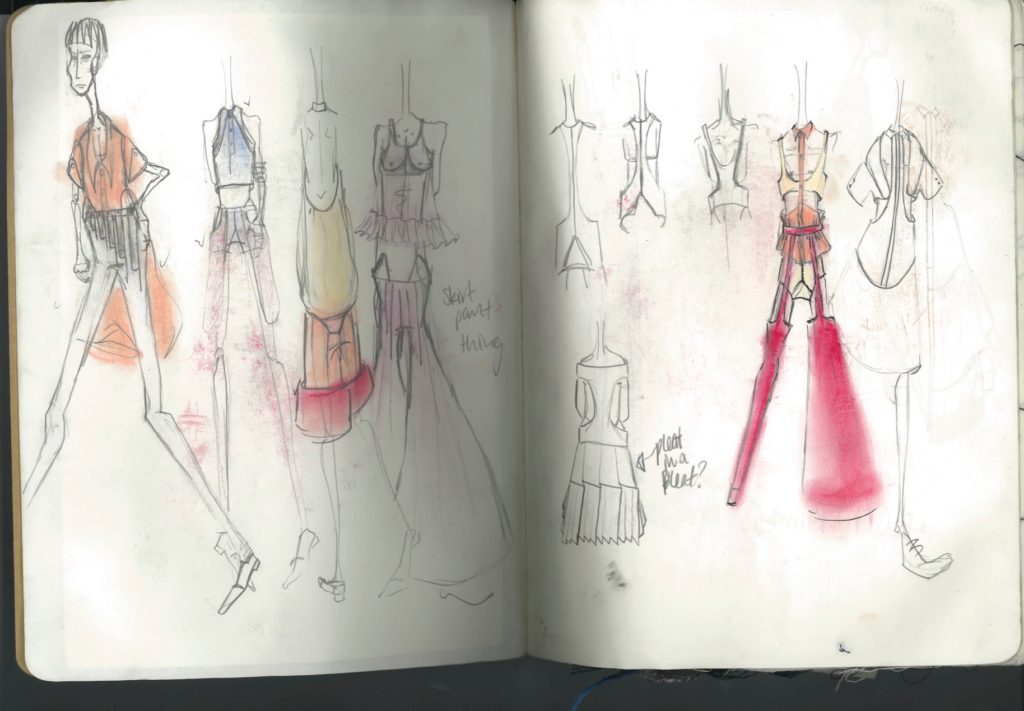

“Most of the time, I don’t give a shit. I don’t need people’s energy,” Aaron says nonchalantly. Apparently, he is used to stares from strangers. It is his livelihood; taking inspiration, communicating it into fashion, and pushing the envelope is pretty much in his job description.

The job at Vince Camuto allows him to establish himself around professionals, who look to Aaron for creative. But his fully realized, undeniable queer fashion sense occasionally brings misunderstandings and isolation. “I’m Aaron first and foremost, and that is how I view everything around me. That is how I dress, I dress from myself,” he shrugs with an unquestionable confidence.

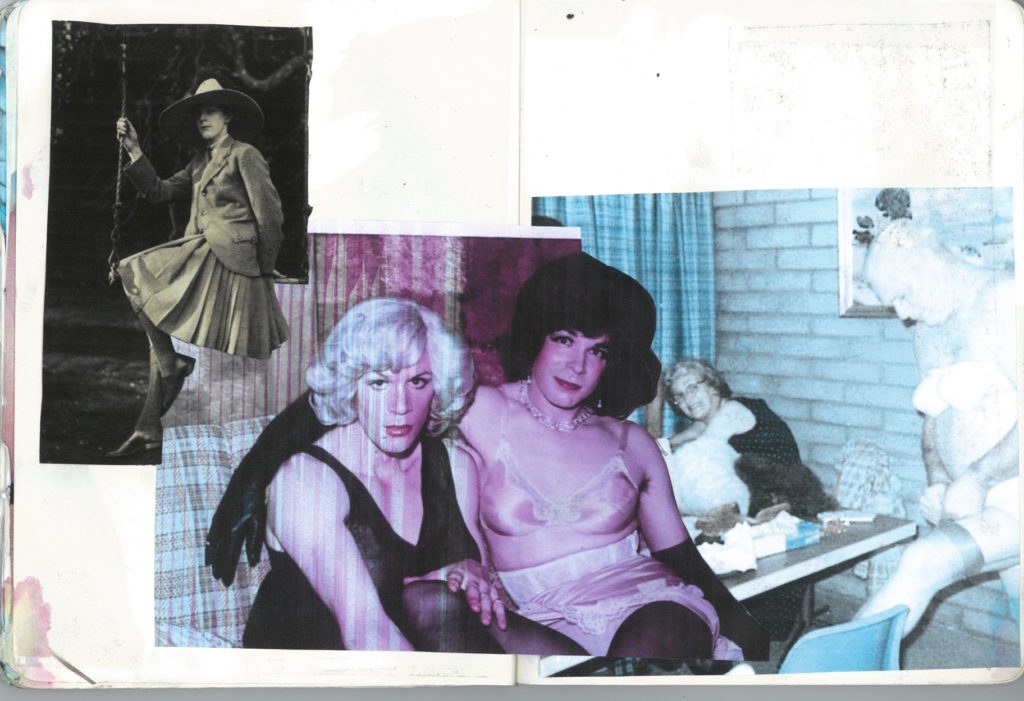

His confidence is supported by the fashion community, at least nowadays. Awareness to social and gender diversity is expanding, due to the increasing visibility of queer culture, as well as the gender revolution happening across multiple areas of our lives. Fashion, in particular, has been an industry that has not only accepted, but actively advocated for a large proportion of LGBTQIA+ pioneers in this creative field.

“Many of the greatest names in XX century fashion were gay or bisexual, including such figures as Christian Dior, Cristobal Balenciaga, Yves Saint Laurent, Norman Hartnell, Halston, etc,” says Shaun Cole, a writer specializing in menswear and gay fashion at the University of London. But while the fashion industry is still stigmatized as being dominated by gay men when it comes to the corporate world of fashion, Aaron says, it’s hardly the case.

Walking into the office, Aaron once again is the minority of his surroundings. Amidst corporate cisgendered men in traditional suits, Aaron is adorned in a light blue frock, accessorized with pink knee-high socks and a bold floral scarf around his neck.

”A ‘higher-up’ once came up to my boss and congratulated them by saying; ’We are so proud of you for hiring a trans-person!’” Aaron recalls with amusement. “It’s funny because that isn’t my situation at all, but for the most part, gender politics is new and I understand why many are confused,” he adds. “When people don’t understand the new realms of queerness, they view everything as an HR victory of an ‘inclusive’ moment,” he says.

This is especially true when a disproportionate amount of men, heteronormative men

For Aaron, working in a corporate environment seems to be important. “Every time I go to a meeting, people have to engage with my queerness in an authoritative way that demands respect,” Aaron shares.

“It is something people need to see. There are people like me out in the world and if I’m your point of contact, I want to be happy and show that I’m a professional person. So what if I’m wearing a skirt or a weird dress,” he expresses passionately.

Aaron, through his words and appearance, expresses a desire to see queer professionals respected, without being forced to change, or worse, driven into seclusion.

“I’m sure that if [colleagues] saw me on the street without any context, it would be a different story,” Aaron admits. “I wouldn’t be interacting with ‘higher-ups’ if I didn’t have some sort of respectability, and, in that way, I like to think I have some visibility when it comes to these people.”

For Aaron, visibility translates into a number of things, be it the seemingly exploitive use of queer identity in media or consumerism, or the fact more and more companies realize that gender-neutral clothing cannot be established until we address the idea of body types in new ways within fashion.

Fluorescent lighting, beige cubicles, and dying desk plants, not unlike the aesthetics of Aaron’s office, now make up the corporate greenhouses for gender-fluid fashion. In the past, the fluid fashion meccas were nightclubs and bars, where the queer community truly flourished. With the millennials and Gen Z workers coming of age, Aaron included, LGBTQIA+ fashion, art and culture are starting to surface within the traditional workplace, in a way that was unimaginable to previous generations.

The gender-bender individuals who previously had no choice but to utilize underground spaces for work, now have an opportunity to step out into the daylight and take a try at leading American companies.

Not everything is rosy, however. Born and raised in Tennessee, Aaron is well equipped to discuss queerness in parts of the world that don’t have the same tolerant history as New York.

“I would argue that rural visibility is more important than queerness in a metropolitan area,” he states. “I think that this rural visibility is why I think the way I do, as far as trying to make queerness visible

“If my voice isn’t for them, then it’s for nobody,” he affirms, stressing the importance of legislation and education.

At work or at home, Aaron is clearly on a mission: “I’m here to normalize queerness,” he says. “Seeing queerness every day will only make life easier, and that’s the hope for each generation that comes next.”

The ‘work’ is a daily process that begins when Aaron steps on the commuter train and continues throughout the day as he engages with fashion executives, challenging how his own work as a designer and advocate is seen by others. “What is professional attire?” he philosophically asks, letting the question to sink into my mind, vaguely unanswered.

Aaron, being incredibly self-reflective, acknowledges his own privileges as a white,

In the workplace, this understanding is even more convoluted. He dreams of “seeing queer people, and specifically young queers, being fearless and self assured, without harassment.” This is the sentiment that guides Aaron through his journey in fashion.

As our society changes, acceptance and visibility of queer identity are becoming a part of the cultural zeitgeist, in a number of manifestations. And yet, the opportunities for understanding and change remain immense. “It’s going to be hard, and you have to be diligent,” Aaron admits. “Since we are in the fashion industry, never compromise your identity or what you wear for anyone, as long as you maintain a professional attitude.”

With similar beliefs about queer

Since the world of fashion is stereotypically perceived as flamboyant and naturally diverse, this optimistic notion can be overlooked— and it shouldn’t.

Aaron teaches us that queer identity doesn’t have to be sacrificed to gain professionalism. Professionalism, no matter the ensemble or accessories, comes from a place of self-acceptance, love

As a young man in a dress, who is establishing what it means to be queer in 2019 while navigating the deep waters of career growth, Aaron is more than a fitting person to teach us this lesson.

Words by Faith Ripoli, BA Fashion Journalism