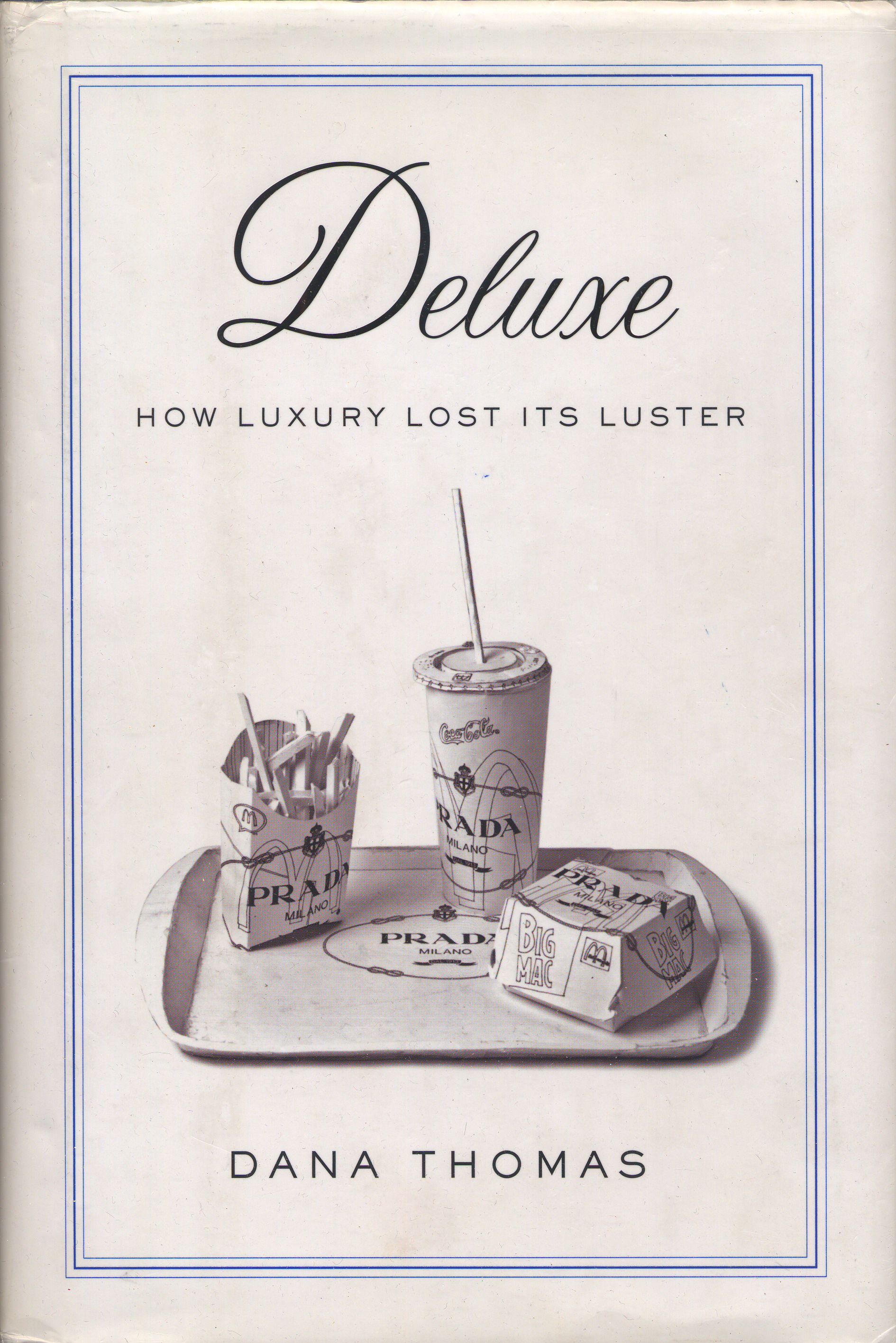

Keanan Duffty talks to Dana Thomas, author of the New York Times bestseller “Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster. Thomas is a contributing editor for WSJ, the Wall Street Journal’s monthly magazine; she began her career writing for the Style section of The Washington Post in Washington, D.C.

From 1995 to 2011, she served as a cultural and fashion correspondent for Newsweek in Paris and has written for the New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, The Financial Times, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Architectural Digest and Elle Décor. Thomas was the European editor of Condé Nast Portfolio. In 1987, she received the Sigma Delta Chi Foundation Scholarship and the Ellis Haller Award for Outstanding Achievement in Journalism.

Keanan Duffty: Since your book “Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster” was published in 2007, the world has experienced a major economic downturn similar to the Great Depression. How do you think this has affected the luxury sector specifically?

Dana Thomas: The downturn whacked the luxury industry at first—sales were sluggish, tastes changed, bling and logos evaporated. It was, for a brief time, no longer cool to show off your wealth since so many people lost theirs. But that lasted two years max, and now the taste for luxury is bigger than ever. You see it on the real estate pages—the mammoth houses for sale at astounding prices. You see it in glossy travel and fashion magazines, with adds and stories hyping wildly expensive destinations and products. And it’s all selling. The downturn made the spread between rich and poor even greater—in reality, it killed the middle class—and the rich got so rich they now spend at a dizzying pace. Proof: Haute Couture has a slew of new young customers who are fine with paying $100,000 for a dress they’ll wear once, maybe twice. At the same time, Asia has boomed, particularly China, and the middle market consumer base has shifted there. Major luxury brands are experiencing record sales in Asia. This is their short and long game for the moment. And it’s making shareholders very wealthy.

KD: What are the key ingredients to launching a European fashion or accessories brand in China or India?

DT: There are a few big differences between Asian and the West when it comes to luxury. Asians—and Japanese in particular—are obsessed with quality. They will not buy something that is not well made, or has a flaw; you won’t see them in an outlet buying rejects at a reduced price. They care deeply about logos—that’s why accessories such as handbags and belts and watches are such big sellers: because they like to be seen wearing a certain product, as if it denotes their class, taste and wealth.

When a luxury company moves into beauty, for Asian they must launch a skin care line rather than make-up; Asian women wear very little make-up, they keep it light. But they are obsessed with their complexions: the whiter and milkier, the better. I have heard that at major luxury companies, when a new product is introduced at a marketing meeting, you will hear: let’s test it in Asian first to see how it plays. And off it goes to focus groups in Asia. If it doesn’t play in Asia, it doesn’t get produced.

I don’t know about India.

KD: Burberry has recently spoken up about a Greenpeace report that some of its children’s clothing contain hazardous chemicals that are believed to disrupt hormones, saying that, “All Burberry products are safe and fully adhere to international environmental and safety standards.”

Do you feel that luxury brands will continue to embrace sustainability and transparency and do you believe the luxury customer cares?

DT: No major publicly traded company will willingly spend its profits to meet international environmental and safety standards; their allegiance is to their shareholders, not the greater good. That’s why watchdog groups and whistleblowers exist: to force, through public embarrassment, companies to adhere to a higher moral standard.

I met a factory owner once who explained it to me. He worked with factories in Madagascar that were cheap in part because their safety installations were next to nothing: the places were rickety, there were no costly fire alarms, security, sprinkler systems, etc. But then there was a factory disaster in the Far East—a factory that produced major American and European brands—and the next-to-nil security and safety regulations were blamed. Several of the brands involved also produced in Madagascar, and told the factory owners there that they needed to install sprinkler systems and cooling systems and fire exits, etc.

The installation and maintenance costs would then raise the price of production to a level that was not appealing to the brands anymore, so instead of sucking it in and investing in making the factories safer, the companies pulled their production from the country and moved elsewhere, where it was safer and still cheap. And the Madagascar manufacturing business and economy collapsed.

You see? It’s all about the bottom line, and that’s that.

KD: On conducting a market test Bernard Arnault, LVMH chairman and Chief Executive Officer, says, “You will never be able to predict the success of a product… Our strategy is to trust the creators. You have to give them leeway. When a creative team believes in a product, you have to trust the team’s gut instinct.”

Do you agree that market testing is not relevant for the luxury sector?

DT: That’s bunk. They all test products. And don’t you believe otherwise.

KD: The prime objective of traditional marketing is raising growth. At Ferrari, production is deliberately kept to fewer than 6,000 vehicles a year. Rarity is valuable so long as the customer understands why the product is rare, and is prepared to wait. Would you say that rarity is the still strongest commodity of luxury goods?

DT: No. And companies like Louis Vuitton, Gucci and Prada prove it. They sell billions and billions of dollars of products every year—and at Louis Vuitton, most sales are of the same products they’ve been selling for more than a century: the monogram line. What makes it luxury in part is the quality (when it is truly made of the best materials and fine craftsmanship), in part the price, and in large part by the marketing. Most of what is called “luxury” today is just overpriced, mass-manufactured stuff. If you really want luxury, have something made just for you.

Interview conducted by Keanan Duffty