Ada Chen is a jewelry and sculpture artist born and raised as ‘Chinese in San Francisco’. She uses her biracial heritage to encourage conversations about her Chinese-American experience, and describes her art as “expensive memes”— a wearable representation of micro-issues often overlooked amid today’s turbulent social dynamics.

It was almost 10 p.m. in New York City when we talked on FaceTime. I often criticize technology for the ironic disconnection it creates between people at the dinner table or at lunch. However, on this occasion, I was only able to have a conversation with Chen — a true, honest talk that felt close to an in-person interview — due to the existence of technology.

Chen had just finished cooking dinner and was doing the dishes. Under the bright, fluorescent light, one half of her face was overexposed for the majority of our call. Although the pixelated quality was a downer, the true quality of our conversation was in her personal stories about heritage, culture and identity as an emerging artist in America.

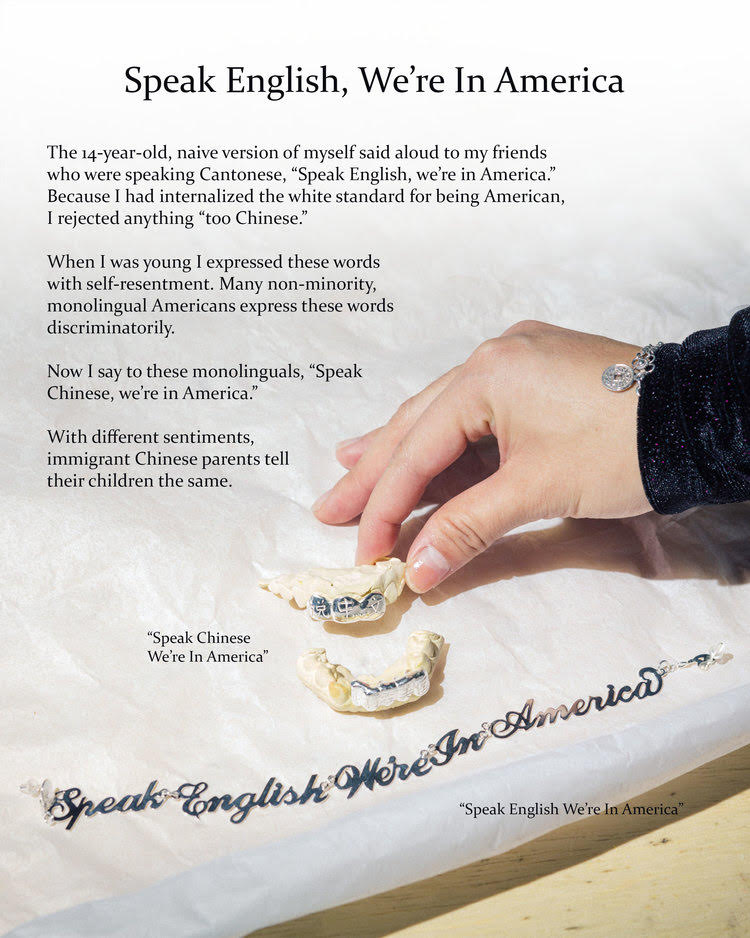

At its core, Chen’s art explores relatability, helping those who feel like they’re part of the minority feel less small and isolated. Chinese-specific household objects and traits such as take-out boxes, jet black hair and mono-lids push forward a multilayered, complex racial conversation.

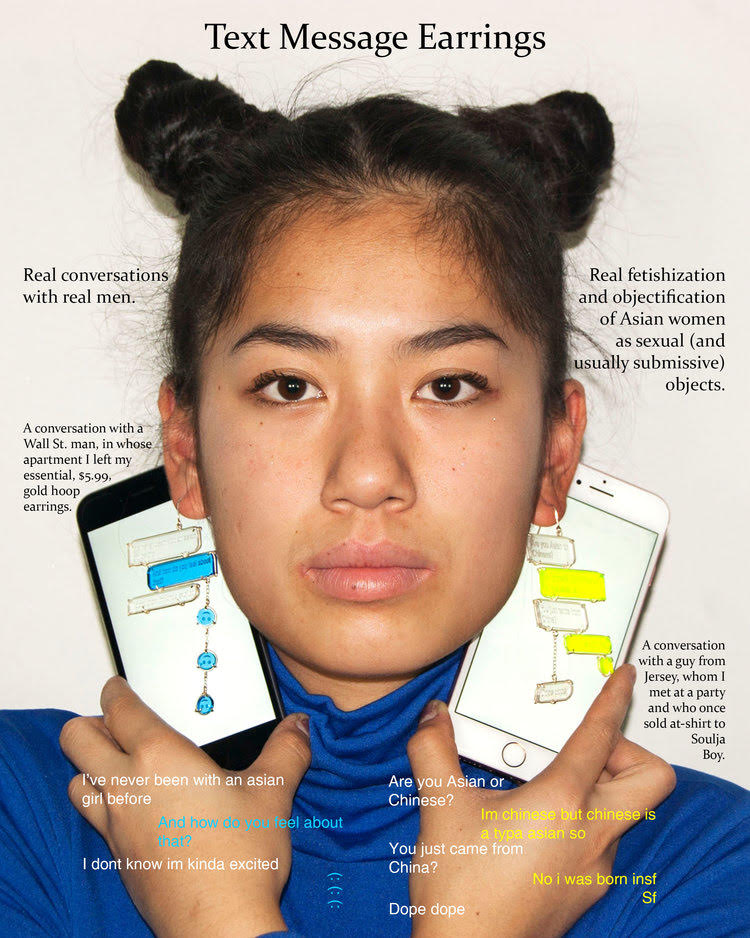

Similar to memes — an art form that inspires Chen — she seeks to create functional art that reaches the public’s psyche and tackles serious conversations in a satirical and quirky manner. A toy drum set, for example, plays off of deep-rooted sexual stereotypes; a cat symbolizes Asian women’s submission; and, a shrimp demeans Asian male masculinity. A ‘chink’ eyepiece pulls back the eyes to mimic the shape of ‘Asian’ eyes.

In my interview with Chen, she delves into topics ranging from school experiences to fetishization.

While you’re American, your Chinese heritage is evident in your appearance and the way were brought up. How much does your heritage define you?

[My heritage] posed a lot of issues when I was growing up and didn’t want to be Chinese. Recognizing that has helped me appreciate how I grew up, and appreciate how much effort my mom put into feeding me every day. It helps me to understand where [my parents] came from and [why] they told me not to go out at night. And it makes me feel less like I’m missing out on a white life that I’ll never have. I know people who have never been to a sleepover because their parents think, “Why would you sleep at a stranger’s house?” And it’s because of that [immigrant] survival instinct. I’m not going to generalize — maybe I am right now — but with immigrant families, they came here because they wanted to escape something else. And it’s this survival mindset that pushes them to be overprotective. So then their children can’t understand it, and they become resentful. It’s the clashing of this “collectiveness” mindset of Asia and the “individualist” [mindset] of [America].

Being Chinese-American, how do you feel about being in the in-between?

I got over it in college. When I started having revelations about my identity, I cared even less.

So you felt a stronger sense of identity in college?

Definitely. In high school, I was really into hip-hop and pop culture. In college, when I met black friends who became my close friends, I noticed that they were super proud of who they are. But I couldn’t be the same proud as them because I’m not black, so [I started] sharing my culture with them and [they did the same]. I think that’s when I started seeing that I have all these great cultural aspects, and I started embracing it. It sucks that it took me moving away from home to do it.

How do you feel about the representation of Asian American artists and culture in the media?

It is definitely not enough. I love “Crazy Rich Asians,” and it has to do with me being East Asian. There’s a lot to be said about having so much pressure to represent all of Asia in one single movie. Even the term “Asian American” is so broad that sometimes it doesn’t make any sense because it lumps the whole continent with all these different countries together. The celebration of Chinese-American culture is rare, because do we even have a culture? That is the question that I always think about. That’s why I gravitated toward hip-hop culture — because I didn’t know if Chinese-American pop culture [even existed]. We didn’t grow up around authentic Chinese culture — we didn’t grow up with that connection to the Forbidden City or the dragon dance. Chinese-American culture is different. It’s basically something like boba.

You use a lot of Chinese inspiration mixed with ordinary American household objects. How exposed are you to your Chinese culture?

I didn’t pay a lot of attention to the Chinese things that my parents showed me growing up. But now that I’m nostalgic about it, I’m a lot more interested. So I’ve been revisiting and watching Chinese drama because it’s so nostalgic. I wish I knew more Chinese songs! I recognize them when I hear them, but I wish I knew their names and the classics.

Are you parents supportive of your career?

They are. But they don’t know exactly what they are supporting. For them it’s about survival. They basically had nothing [before], so they’re like, “How can my child succeed?” because this country is so much about money. I feel very lucky to have a dad who wanted to do art [in the past]. The second I took interest, he was super supportive because I’m [now] living the dream he never lived.

How much do memes and internet culture inspire your art?

It’s super inspiring because if you think about it, someone still had to make that. Someone put together all these puzzle pieces of society — they noticed and they put them together in a way that is relatable to other people. Memes are an art form because somebody created them. All these images just come out and become viral, and then they become formats for other ideas to exist within the same surroundings and the same social context. I would describe my art as expensive memes.

How would you describe your aesthetic? There is a repetition of metal and bold colors with provocative messages.

There’s no reasoning behind it except my own taste. You can do more with colors and they’re more interesting and eye-catching. I just can’t get into nude colors. They’re boring. And I was just talking to [writer and jeweler] Kelly Riggs. I’m working with her for New York City Jewelry Week. She said, “You know, traditional academic jewelry is always placed on a white background to shove your attention [toward] the jewelry. It’s like, ‘Look at this piece, this object on a white background.’” And it’s always the white background; it makes no sense. Why wouldn’t you [give] context to the piece? So I place my objects in context. It also has to do with me not making “aesthetic” work and making it more about a concept, because usually jewelry is the thing you see that’s pretty. That’s all there is to it. And yeah, the craft is good. But can you say something more?

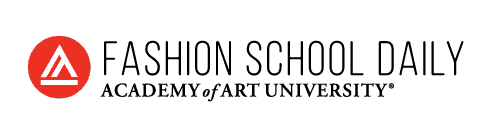

Tell me about the context of “text message” earrings and the meaning you put into them?

Those [text] conversations were actual conversations with men fetishizing me. I hate when non-Asian men just point out the fact that I’m Asian, because then I know that that’s all what they see. Obviously, that comes from a fetishization standpoint because this is what they’re focusing on. It’s ignorant, because you’re only saying these things when you don’t know that it’s disrespectful, right? So someone has to say something about it, because it’s not anyone’s job to teach someone how to not be problematic. It takes a certain person to do it, and I’m fine being that person.

Have you received any negative feedback?

Yes! The most significant ones were Asian men. One of them said, “Your eye piece is not beautiful. I don’t know who you’re trying to convince that this is art, but this is ugly.” And I basically just replied, “Because you think this is ugly — that’s why I made this piece. It’s because you think that ‘chinky’ eyes are ugly.” He didn’t respond.

There were a lot of comments on [my text message earrings] specifically about Asians dating white men, even though the real conversations I had weren’t with white men. There is a lot of turmoil just within the Asian community itself because Asian men can be resentful. I’m often very solid about my ideas and what my intentions were, so if the [response] doesn’t match up, I’ll just be like, “Sorry, you didn’t get it.”

Instead of jewelry design, you initially applied to study fashion in college. Why the switch?

I was just thinking about the industry and the competition. It didn’t seem worth it to pursue [an overly critical] field [or] a community that didn’t fit me. It sounds corny, but I just didn’t like the vibe of the industry.

When did you start to explore metal smithing?

I wanted to try something new, so I started metal smithing in college. I went into it without really knowing how to do anything, and I liked that challenge. I felt like I’d already done everything else. I was like, “Where else am I going to learn how to make jewelry?”

What are you working on now?

I graduated and I got a job a month later. I work for a company and I make their jewelry. It’s a nine-to-five, Monday-through-Friday production job. I’m not meant to do that [in the long term]. Early on I [realized] that I need to build experience in this industry. At the same time, my work kind of blew up and I started making more earrings because they were selling. New York City Jewelry Week is giving me the opportunity to build my voice as an artist. These things are all happening at the same time, and I feel like I can’t do both. It’s a struggle to fulfill myself and balance my job, which I need for money. I got a spot at a shared studio space, but then I realized — realistically, how often would I go there after work? I’ll be tired. It’s the same thing that every artist goes through. I’m trying to work on myself and at the same time [am doing a job] I don’t like as much to support myself.

Are your pieces made to order?

It’s really expensive to use a laser cutter so I’ll always just cut a lot at once. The last number I had was 30 — [that’s] how many I could fit on a piece of 12-by-12 acrylics. Then when people order a pair, I put them together. Since I have a full-time job, I can’t really keep up a lot of the time. It [still takes] me about two to three hours to make a pair.

How long does it take for you to work on a piece? What is the process like?

Hella long. That’s one thing people people don’t [realize] about jewelry, because it’s metal and it has to function. Just one of my slippers took 63 hours to make. I made that from a sheet of silver and metallic wires. For the text message earrings, I used a laser cutter. I think that’s why people don’t do jewelry that often, because [the resources] aren’t as accessible, unless you really go to school and learn about it. You can’t just have a [soldering] torch in your house without knowing how to use it.

Do you plan to explore any other mediums?

I have no permanent interest in jewelry. I have taken classes that were more inspirational to me than jewelry, but they have nothing to do with a lot of my work. I loved my woodshop class, but that has nothing to do with my voice as an artist. And I loved my photo class, which kind of seeped into my thesis. A big part of me being able to create those images was having taken that photo class. I definitely want to keep it on a sculptural level, and it’s not like I’m dissing jewelry, because it’s a great medium.

Do you plan to start your own jewelry line?

I mostly want to work for myself, but I don’t really want to just do production and commercial pieces. I want to make one-of-a-kind pieces that will make a statement. I really want to make jewelry accessible, which means that they can relate to it in different ways. I’m more interested in pieces that express my thoughts and things that I discover along the way about myself and my identity. But then there’s also the capitalist reality of our world. I can’t just have pieces in a gallery and survive, because then I’ll be broke forever.

Words by Anna Nguyen, BA Fashion Journalism